Maurice Sendak, died May 8, 2012, at the age of 83 from complications of a stroke according to The New York Times.

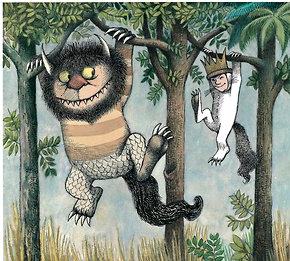

The name might not be familiar, but his work is. Sendak, is most famous for his book “Where The Wild Things Are.”

Other works by Sendak include “In The Night Kitchen,” “Bumble-Ardy” and “Outside Over There.”

NPR’s show Fresh Air dedicated the entire program to Sendak by airing previous interviews with him.

Past the subdued fog and alluring designs of his books, his writings deal with deeper issues.

Sendak created a protagonist child that battled the conditions of being a well-mannered and groomed character who triumphed in an attractive manner. His characters, which would exist in creative dreamlike circumstances, would bring the reality of life into childhood.

Sendak broke boundaries with his writings and illustrations that brought the reality of monsters into children’s book.

Sendak grew up in a Jewish home, where Yiddish was spoken, and lived with his relatives that were brought over by his parents because of the Holocaust.

In a 1986 NPR audio interview, Sendak spoke about his childhood.

As a child, Sendak said he had fears that were different than others. The vacuum cleaner, when turned on, became a huge monster that billowed and was very frightening. After watching the 1933 movie, “The Invisible Man,” he became petrified of the Invisible Man who became “[the] most terrifying [fear] and led to being an insomniac for rest of life.”

As a child he saw adults as “…big and grotesque… and couldn’t see it happening to him.”

Later in the interview, he suggested that being a child is hard–not as simple as adults think. “Being a child was a creature without power, pocket money, escape routes of any kind, so I didn’t want to be a child. [I] remember as a small boy taken to see a version of Peter Pan; I detested it. [The] sentimental idea that anybody would want to remain a boy forever, [I] couldn’t think it out then.”

As a child he said he detested that “all his Jewish relatives” were “all adults who treated us in such silly fashions.” In turn, he asserted that children are overly harsh about physical abnormalities, so he took the physical attributes of those relatives into his illustrations for “Where the Wild Things Are.”

But Sendak does reflect on some happy memories he had with his only grandmother and her windows. Since he spent a lot of time indoors due to sickness, he would sit on his grandmother’s lap and used the window as his version of a movie or television set.

In one of his last interviews in 2011 with NPR, he delved into the making of “Bumble-Ardy.”

Sendak said that while growing up, he had the same troubles as Bumble-Ardy in a different context. Sendak had an older brother who saved him from the complexity of his childhood and helped him endure it. His brother “drew [him] away from lack of comprehension from [their] parents.”

His brother took time to do enjoyable activities, and sometimes his sister joined. Unfortunately, his sister had “to concentrate on what was expected from [their] parents.” Life with his brother “contradicted the prosaic life of what (Sendak) was expected to be,” “to shut up and be a quiet kid.” Sendak resented that upbringing for a long time but admitted that he no longer did.

Sendak said “Bumble-Ardy” was “a combination of deepest pain and wondrous feeling of coming into own and took a long time and is genuine.” Furthermore, he said “Bumble-Ardy” dealt with the “fragility of life, irrationality of life [and] comedy of life.”

In death, Sendak said he believed there is no life after or another world. He said he was not afraid of death and was not unhappy about becoming old but said he had difficulties dealing with the death of those close to him.

The complexity of being young and growing old is something we all deal with, and Sendak dealt with such things through story.

Maurice Sendak opened up a new world for children’s books. His writings and illustrations were influenced by his life and worldview. He managed life’s pain and joys through his art.

The NPR segment can be found here.

Images from www.nytimes.com and www.harpercollinschildrens.com