Pastor Khem Sam reminds his congregation that “we are the lucky ones” every Sunday at Belmont Heights Baptist Church. Those may be just words to most, but to Pastor Sam, those words hold a much deeper meaning.

Sam was abandoned by his parents as a young boy. He struggled to survive on the streets of poverty-stricken Cambodia. That was just the beginning of his problems.

“I did whatever I could to survive,” he said. “I took whatever jobs I could find.”

One of Sam’s first jobs was as a taxi driver. The only difference with today’s taxi drivers and those in the 1950s and 60s Cambodia was that they did not use cars. Sam would sit passengers in a carriage and he would walk or run them around town for miles in a day.

Sam eventually worked hard enough to pay his way through school. “In those days only the rich people went to school,” he said. “The poor were illiterate, and I knew that I had to educate myself if I wanted a better future for myself.”

Then came the Vietnam War, and Sam’s world would turn upside-down. Cambodia was a neutral country during the war, but it was often bombed by American forces because its borders were used as a supply chain to the North Vietnamese.

It is estimated that as many as 500,000 Cambodians died as a direct result of the bombings, while perhaps hundreds of thousands more died from the effects of displacement, disease or starvation during this period.

After the Vietnam was over, the Cambodian government collapsed and was taken over by the Khmer Rouge guerrilla movement led by Pol Pot. It was during this time that Sam would face his toughest obstacles.

“The Khmer Rouge put everyone into camps and made them work to death,” said Sam. “They killed anyone who spoke up against them, or anyone who refused to leave their home.”

Sam knew that he would not last long working in the camps, and as a Christian, he knew that his time was even more limited. He decided to take his family and make a run for the free borders of Thailand.

“We had no choice, this was our only chance to survive,” he said. “We went with a group of people, but we didn’t all make it.

“I carried my son on my shoulders and covered his mouth (to muffle the noise from crying). If soldiers heard us they would kill us on sight,” he said. “We also had to watch where we stepped because landmines were everywhere.”

Sam would eventually make it with his wife and son to a UN refugee camp in Prachin Buri, Thailand. They would stay in the refugee camps for another four-years.

“Refugee camps were rough, people died everyday from disease and starvation,” he said. “There just wasn’t enough food and medicine to go around.

“I saw dozens of people die every day, and thousands during the four years we were there.”

Sam could speak English, and his education would become helpful as he became a translator for the UN nurses.

“Everyone had to find a job at the camp, my job was to translate,” he said.

Sam’s family would grow in the refugee camp. He had two daughters and one son in addition to the son he already had.

Conditions were harsh and it was tough to raise kids in such poverty.

“Malnutrition and parasitic diseases claimed the lives of many children in the camped and almost claimed the life of my youngest son,” he said. “I was lucky enough to have a nurse who really cared for my family and she was able to find medicine for my son when he was really sick.”

The Sam family would later be sponsored by a church in Knoxville, Tenn. They finally got their chance to come to America.

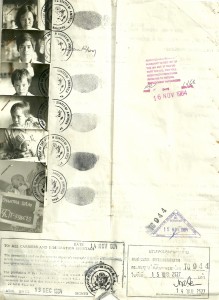

“We had to take a lot of tests before we came to America. They wanted to make sure we had no ties to the Khmer Rouge,” said Sam.

Sam and his family would land in New York City on Nov. 17, 1984. He remembers it as the coldest day in his life.

Sam and his family would land in New York City on Nov. 17, 1984. He remembers it as the coldest day in his life.

“The coldest it ever gets in Cambodia is around 60 degrees. I was freezing in New York,” Sam said.

The family would eventually settle in Knoxville for a couple years until Sam was offered a job in Nashville.

“God came calling, and I was offered a position as the minister of the Cambodian mission at Belmont Heights Baptist church,” he said. “There is a purpose to everything that happens in our lives. This was my purpose.”

The congregation has about 80 members and continues to grow.

“I pray that the Cambodian people here in Nashville will come to accept Christ,” he said. “We all have similar stories. We are the lucky ones.”

The Cambodian genocide would claim over two-million people and thousands more would die in refugee camps. Over a quarter-million Cambodian refugees now reside in America.

Pastor Sam celebrated 22 years at Belmont Heights in January. He has only missed one sermon in those 22 years. The one day he missed was when he went back to Cambodia to bury his mother — the same mother who abandoned him almost six decades before.

The author, Monaih Sam, is the son of the article’s subject.