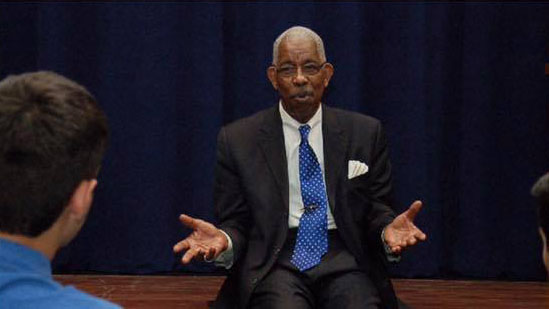

In a chapel meant to foster cultural communication, racial reconciliation and acceptance, Freedom Rider Dr. Rip Patton spoke to students about his fight for desegregation through nonviolence.

“Nonviolence is a way of violence,” Patton said to the group of students gathered. “It’s a way of fighting — fighting with love.”

During his sit-down in Multicultural Awareness Skills and Knowledge (MASK) chapel with Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Norma Burgess, Patton began the conversation before the first question was asked by drawing a contrast between what Lipscomb students see every day on their walls with what he saw as a college student in segregated Nashville.

“I’m sure we’ve all heard the prayer, but when I first walked in through those doors, I saw this up here,” Patton said, gesturing to the words of Mark 10:45 embossed into the top of the stained-glass window in Ezell chapel.

“‘I did not come to be served, but to serve and give my life as a ransom for many.’ Think about that,” the Freedom Rider said. “Put yourself in that place. That’s what happened here in Nashville in 1960 through 1964. It took us about four years to desegregate everything in Nashville. Everything you could think of was segregated.”

Freedom Riders are those who boarded the buses heading to the most notably segregated cities in the South to challenge Jim Crow laws by using peaceful means in 1961. The rides were a tactic established and organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) aimed at desegregating public transportation in the South after the Supreme Court ruled segregation in interstate buses and rails unconstitutional.

The majority of Freedom Riders were between the ages of 18 and 22, and many were first generation college students only a semester away from graduating who chose to join the movement at a crucial part of the semester.

Through their rides and sacrifice, the groups of students were met with deep-seeded hatred and violence in the southern states. One of the earliest buses was firebombed in Anniston, Alabama, by a mob aided by local police and members of the Ku Klux Klan who badly beat many Freedom Riders.

Although some thought this highly publicized tragedy would be an end to the movement, it was only just beginning for Patton. As a 21-year-old drum major from Tennessee State University, Patton found motivation in the setback and joined the next group of Freedom Riders headed south.

“We learned about nonviolence because Jim Lawson was our teacher,” Patton said. “Jim Lawson had studied in India, studies the methods of India and was a missionary in India for three years. So we just followed what Gandhi did.”

In addition to studying methods of nonviolence, Patton said the students found peace and patience through song, a peace that can still be seen and felt today in his presence, voice and tone.

“We learned a lot of songs, and if you know anything about music, sometimes when you’re just sitting you’ll fade off into a song,” Patton said to the group. “You’re not singing it out loud, but it’s just something that you hear in your head, and so we learned how to do that. When somebody was either hitting you, trying to put a cigarette out on you or pouring hot coffee on you, we sang.”

While Patton and many other students faced unthinkable circumstances with bravery and motivation, he still believes there is work to be done and nothing is too big or too small for this generation of students to get involved in.

“Hopefully they know that they can make a change. There’s a lot of work to be done. The fight is not over, and if they can make a change, do it nonviolently,” Patton said.

For today’s Lipscomb students, recent opportunities to join marches and protests in Nashville has inspired some to bring deeper cultural awareness to Lipscomb’s predominately white, Christian campus. Among those is MASK chapel coordinator Mason Borneman who helped get Patton to speak on campus.

“I think it’s important for Lipscomb’s campus because we have to keep in mind that Christianity does not have one color or background,” Borneman said.

“We have to understand that whenever we reach across different cultures and backgrounds, we all have a common human experience that links us. That’s when real growth can happen, and that’s what we foster here.”

After spending the first week of Black History Month taking advantage of the opportunities to engage in cross-cultural communication through attending speaking events, documentary screenings and meeting those from other cultures, Lebron Hill says for these important conversations to start, students “should talk to someone who doesn’t look like you.”

“All these things we do — whether it be watching 13th or listening to someone speak about their experience in the civil rights movement — it’s all about trying to engage,” Hill said. “Try to talk to someone who is African American or any color, see where they’re coming from and get to know them.”

Lipscomb students will have the chance to do just that at MASK chapels and other opportunities sponsored by the Office of Intercultural Development throughout the semester.

For more information on Freedom Riders and other stories of the movement, the documentary Freedom Riders is available for free online featuring Patton among other activists, historians and witnesses.